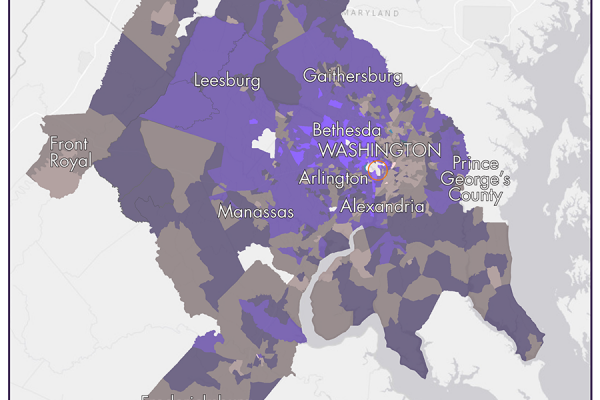

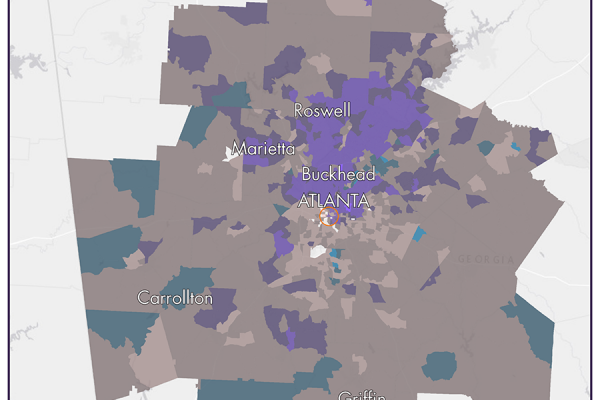

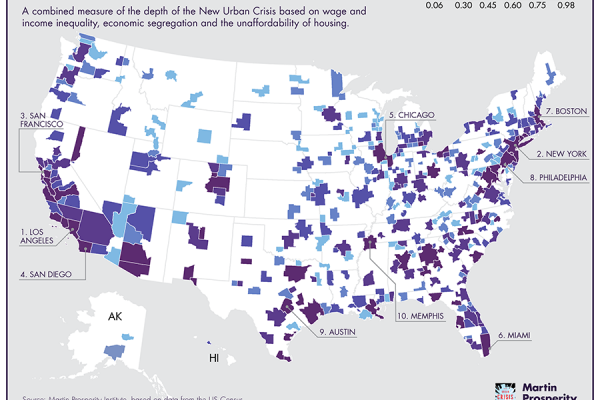

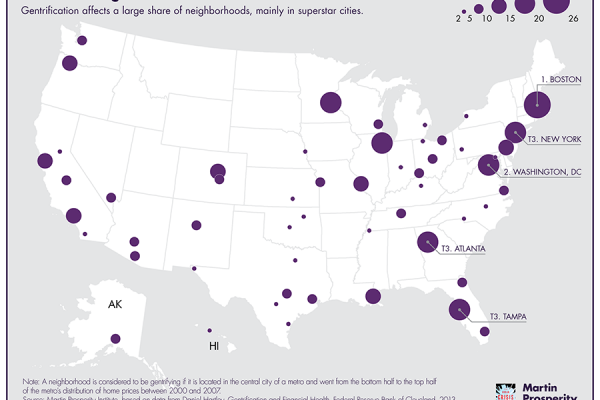

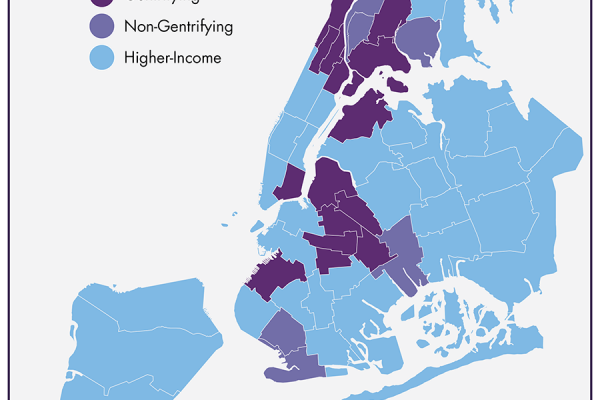

Runaway gentrification. Concentrated poverty. Racial and economic segregation. Cities in the United States today are struggling with some of their biggest challenges since the darkest days of the 1960s and 1970s, when “white flight,” deindustrialization, and crime were at their peaks. Together, these concerns add up to what I have dubbed the New Urban Crisis.

The New Urban Crisis

How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class-and What We Can Do About It

By Richard Florida

“Intellectual rock star” Richard Florida confronts the dark side of the creative economy he celebrated in The Rise of the Creative Class, and grapples with the gentrification, inequality, and segregation it has created in our cities.

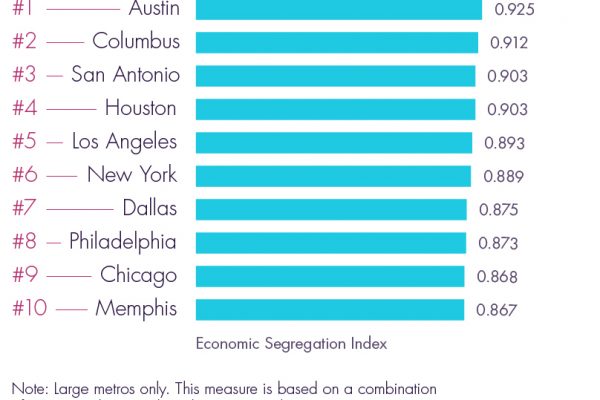

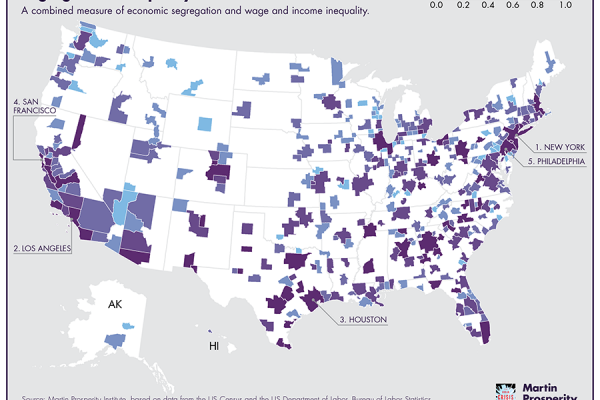

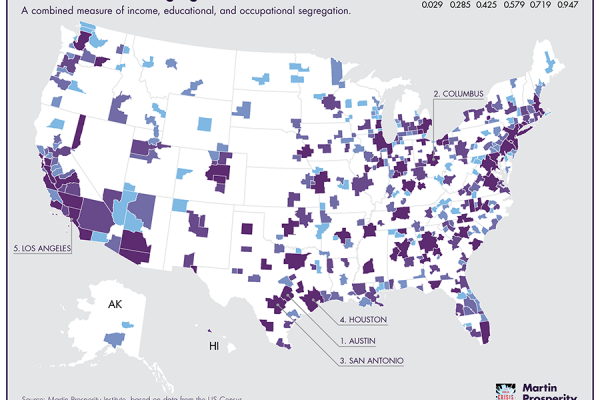

In recent years, the young, educated, and affluent have surged back into cities, reversing decades of suburban flight and urban decline. And yet all is not well. In The New Urban Crisis, Richard Florida, one of the first scholars to anticipate this back-to-the-city movement in his groundbreaking The Rise of the Creative Class, demonstrates how the same forces that power the growth of the world’s superstar cities also generate their vexing challenges: gentrification, unaffordability, segregation, and inequality. Across nearly every metro area, middle-class neighborhoods are disappearing. Our cities and suburbs are being replaced by a patchwork metropolis, in which small areas of privilege are surrounded by vast swaths of poverty and disadvantage. The rise of a winner-take-all-urbanism, with a small group of winners and a much larger span of losers, signals a profound crisis of today’s urbanized knowledge economy that threatens our economic future and way of life.

But if this crisis is urban, so is its solution. Cities remain the most powerful economic engines the world has ever seen. The only way forward is to devise a new model of urbanism that encourages innovation and wealth creation while generating good jobs, rising living standards, and a better way of life for everyone. We must break down the barriers separating rich from poor and rebuild the middle class by investing in infrastructure, building more housing, reforming zoning and tax laws, and developing a new national urban policy.

A bracingly original work of research and analysis, The New Urban Crisis offers a compelling diagnosis of our economic ills and a bold prescription for more inclusive cities capable of ensuring growth and prosperity for all.

In The Rise of the Creative Class, you argued that luring talented members of the “creative class” was the key to reviving cities. You now reject that optimism you once had in THE NEW URBAN CRISIS. Why?

I haven’t altogether rejected my optimism, though it has been tempered, both by what I’ve learned in the course of researching and writing this book and by the election of Donald Trump, which is a product of the huge divides I identify in the New Urban Crisis. My work has been a progression. The Rise of the Creative Class was one of the very first books to recognize the stunning revival of our cities and the new class of knowledge workers and professionals and creatives that are driving it. But as that urban revival has progressed, it has generated deeper divides, more expensive housing, greater segregation and a host of deep and distressing challenges.

Cities are still the most powerful economic engines the world has ever seen, and they are bastions of diversity, tolerance, and progress. But the very same force that drives the growth of our cities and economy broadly also generates the divides that separate us and the contradictions that hold us back.

It all comes down to the competition for scarce urban land, which drives up housing prices, creating vast geographical as well as economic inequalities within cities and widening the gaps between them. It’s hard to sustain a functional urban economy when teachers, nurses, police officers, firefighters, and restaurant and service workers can’t afford to live in it. When no one but the rich live in a city, it loses its innovative capacities. As Jane Jacobs once told me, “When a place gets boring, even the rich leave.” I do believe that with sufficient will and focus, and the right institutions, policies, and investments, it is still possible to forge a more inclusive urbanism. But cities are going to have to fix their problems on their own. The federal government is not coming to their rescue. In fact, it’s likely to stand in their way.

What served as a wakeup call for you?

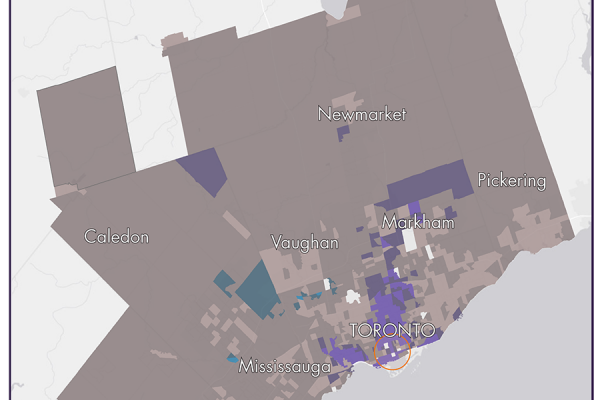

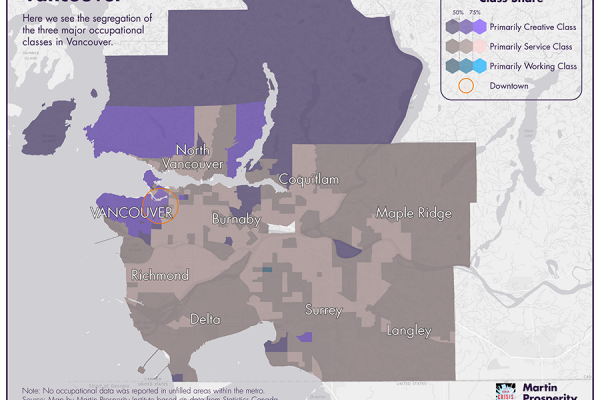

I had two “ah-ha” moments. The first was when I moved to Toronto to run the Martin Prosperity Institute at the Rotman School at the University of Toronto. Toronto is the most diverse city in North America. It is a model of progressive urbanism, and was praised as such by Jane Jacobs, who lived there in the last decades of her life. Yet it elected Rob Ford as its mayor, on a platform that was not just reactionary but explicitly anti-urban. If as progressive and creative a city as Toronto could experience such a powerful backlash against the engine of its prosperity, then what might we be in for elsewhere?

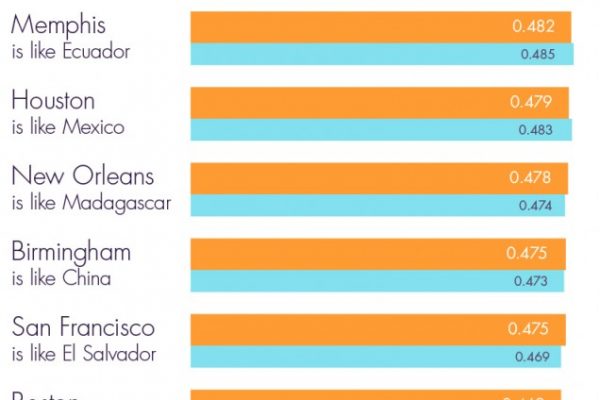

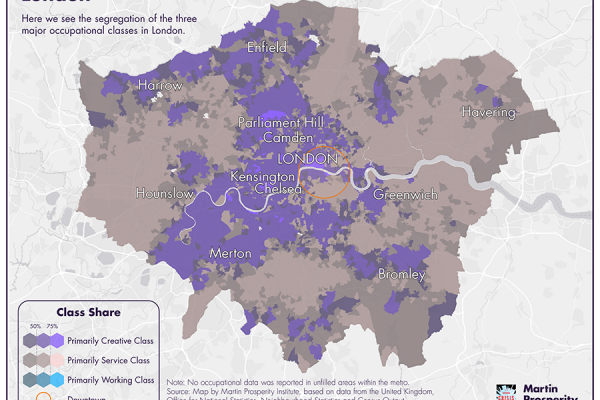

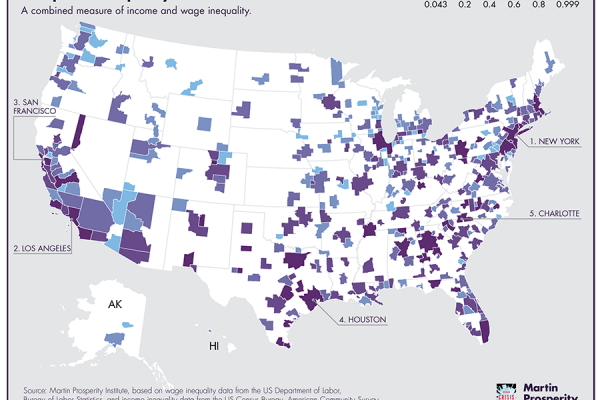

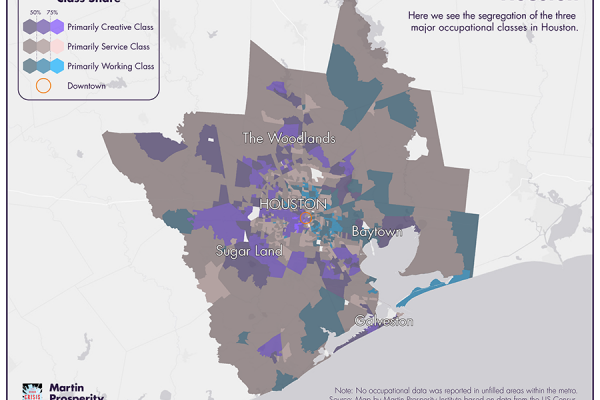

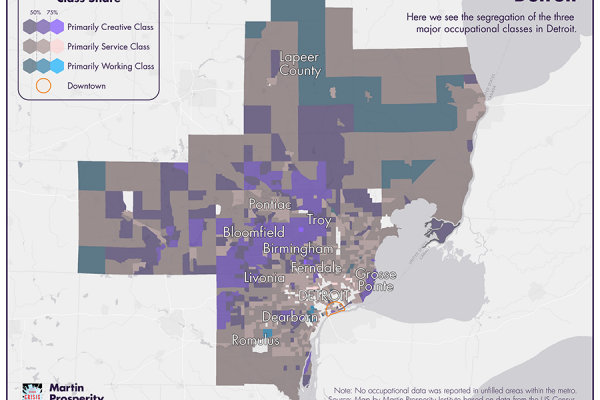

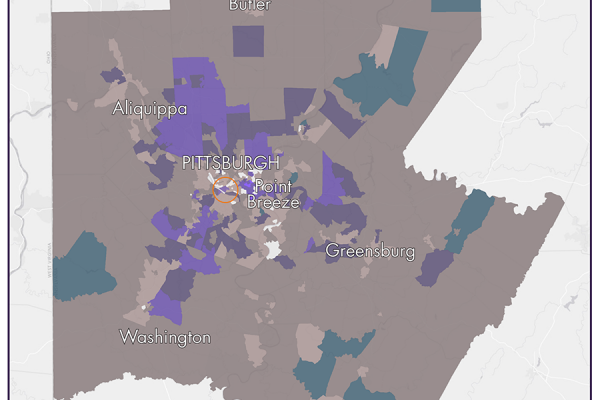

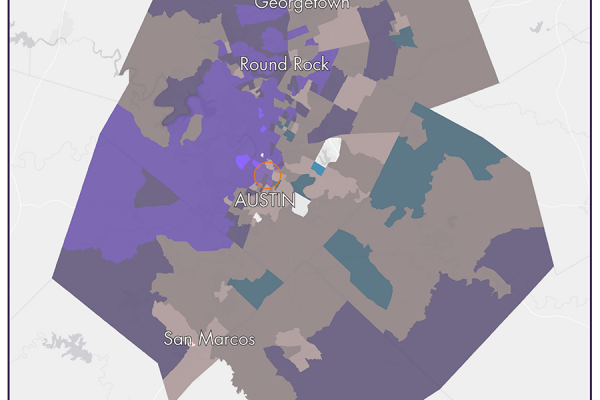

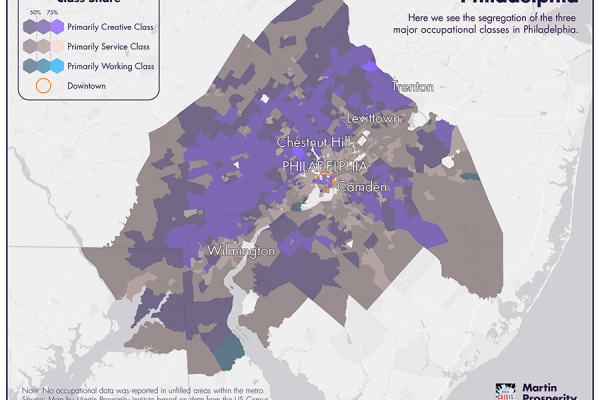

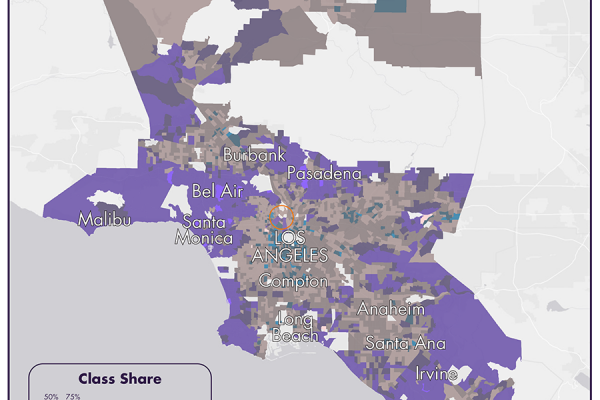

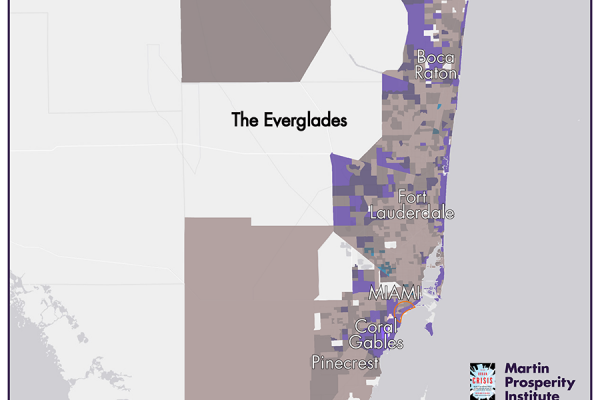

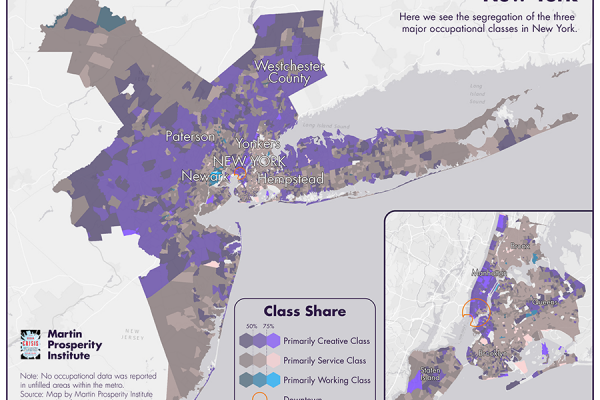

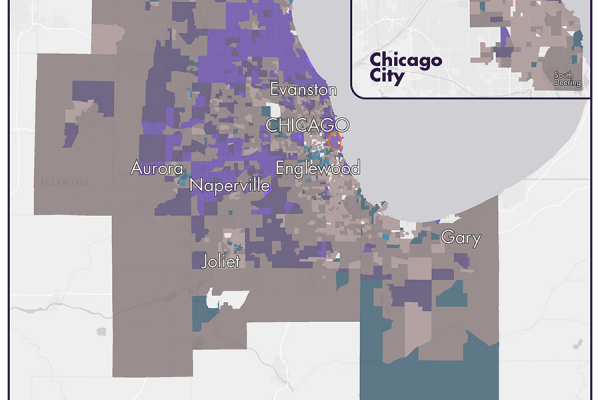

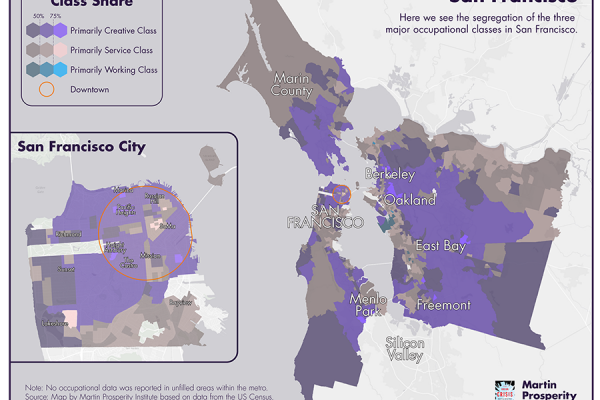

I had long been interested in inequality. And have been researching inequality for the better part of a decade. I pointed to the growing separation between the classes in Rise of the Creative Class. And in the early 2000s I wrote an essay for the Washington Monthly where I found that the cities and metros with the largest creative class also had the highest levels of wage inequality. But my second big “aha” moment came when I colleague and I decided to look at what happens to the economic situation of the three major classes – the advantaged creative class and the less advantaged working and service classes – when we take housing costs into account. The creative class has more than enough left over to live well, but the blue collar working class and especially the service class—which together account for more about two thirds of the workforce got killed. You can see the numbers in chapter 2 of the book. They are staggering. The average creative-class worker in San Jose has $80,503 left over after paying for housing, while the average service-class worker ends up with just $14,372. In New York, it’s $71,245, compared to just $17,861.

What challenges do our cities and suburbs face thanks to the urban shift?

The big, rich cities and the thriving knowledge and tech hubs—the New Yorks, Parises, Londons, and San Franciscos of the world—face something of a “crisis of success” if I can put it that way. As the affluent and the educated have come back, their housing prices have risen and they have become less affordable and more divided. But a much large group of cities – including older Rustbelt cities and sprawling Sunbelt places – are still economically challenged. And of course, things we once thought of as quintessentially urban problems – like poverty, economic distress and crime – have spread into the suburbs. In many ways the crisis of the suburbs is a bigger dimension of the New Urban Crisis than what is happening in urban areas, both because it is so recent and more so because more people live in suburbs than cities.

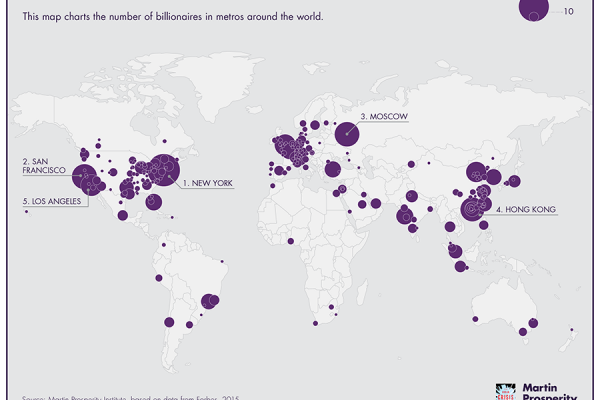

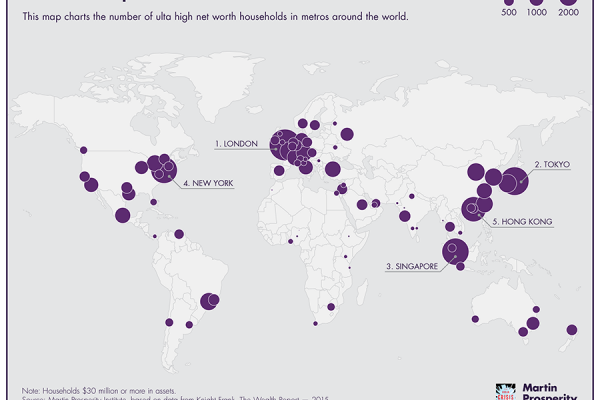

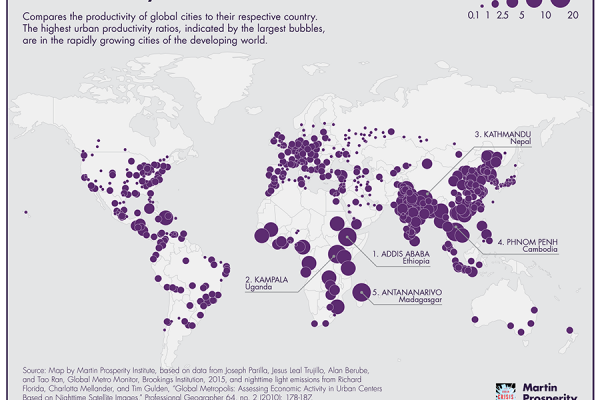

The book also identifies the crisis of global urbanization as perhaps the biggest dimension of the New Urban Crisis of all. 860 million people live in the global slums of rapidly urbanizing cities in the developing world – that’s more than the population of the US and the European Union combined. For much of the 20th century – in the US, Europe and Japan – rising urbanization went along with a growing economy, rising living standards and the growth of a middle class. That is no longer the case in many parts of the world that are rapidly urbanizing. Today we are seeing a distressing process of “urbanization without growth” where places urbanize but stay poor. This is perhaps the grandest of all the grand challenges the world faces.

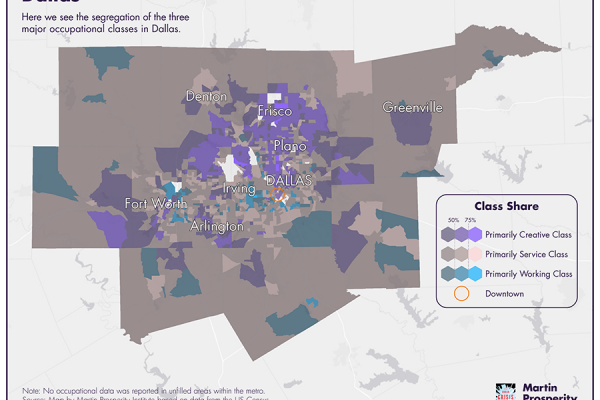

Can you discuss the job bifurcation within cities and among cities?

We hear a lot about rising inequality and the fading of the middle class. And all of that is true. Globalization, automation, outsourcing and the like have led to the decline of once high-paying middle class factory jobs and the bifurcation of our economy into high paid knowledge jobs and low paid service jobs. (I identified all of that a decade or so ago in Rise of the Creative Class).

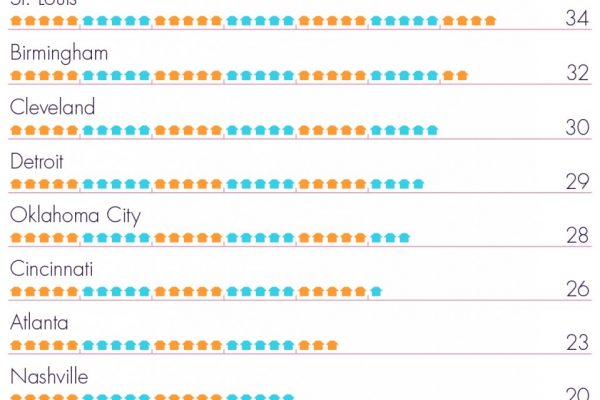

But that bifurcation is now being etched into the way we live. It is not just the middle class that is fading, but the once sturdy middle class neighborhoods that were the anchors of the American Dream. The book has the data on this and it is staggering.

Can you give some examples of housing and infrastructure challenges?

Both housing and infrastructure, as well as upgrading low-wage service jobs, are key to solving the New Urban Crisis. In the book I identify the Urban Land Nexus as a central contradiction of the New Urban Crisis. The world is filled with land, most of it unoccupied and undeveloped. But because of the economic effects of urban clustering – of people, knowledge and industries, – which by the way is the basic driver of innovation and wealth today, so much stuff seeks to cram itself into tiny slivers of land in cities like New York, London and San Francisco. In doing so, it crowds everything else out, raises housing prices and divides us. The super-rich colonize the best locations, the techies and professionals get the next best, the middle class, the working class and the poor are pushed out.

So we need to build more housing. That requires more density. But right now our expensive cities are rife with NIMBYism, or what in the book I dub, the “New Urban Luddites” and the “New Urban Luddism.” I call them this because not only do they block housing development; like the original Luddites who smashed the machines in factories, the New Urban Luddites are holding back the innovative and wealth-producing capacity of our cities.

For a growing number of policy-makers and economists the solution to all of this lies in getting rid of the zoning and building codes, the land use restrictions that make it hard to build denser, taller buildings in these cities. They are right up to a point. But as the book shows, too much density and too many tall towers can create a kind of “vertical sprawl” of condo canyons that you see in Asian cities. What is truly short supply are the old industrial neighborhoods with mixed use warehouse buildings, places like New York’s Chelsea and SoHo or San Francisco’s SOMA which are where artists, creatives and innovators gravitate. We have to be careful not to throw the proverbial nay out with the bathwater. Not to mention radical deregulation of land use will also likely result in more luxury buildings going up and very little in the way of affordable housing for the middle and working classes. So we need the right kind of density and we need to shift from our current system that subsidizes homeownership for the affluent to one that creates more affordable rental housing.

The only thing Donald Trump gets right is that our urban infrastructure is crumbling. The reason so many affluent people are moving back downtown or around subway stations is that we haven’t built transit infrastructure of any magnitude for the past century. We need to invest in transit and high-speed rail to connect outlying suburbs and even outlying cities to our urban economic centers. That will enable to live further out where land and housing costs are cheaper, expanding the labor markets of our great cities..

What are some of the hidden challenges of the poor living in the suburbs?

are already more poor people in suburbs than cities. And the costs and challenges are many. For one, lower income workers in the suburbs are further removed from centers of work; they have a harder time finding jobs and getting to and from them than poor workers who are able to live in cities do. And they are equally disconnected from social services. Large numbers of the suburban poor have a hard time even admitting that they are poor, since they were middle class before the jobs went away and their mortgages sank underwater. Suburban police departments are much less equipped to handle crime. Not to mention the huge costs that sprawl generates for the economy writ large. As the book points out, the suburban dimensions of the New Urban Crisis are bigger – and growing faster – than the urban ones.

What are some necessary steps that need to be taken to address urban and suburban inequality?

In addition to building more housing and particularly to building more affordable rental housing and to investing in transit to connect outlying places to vibrant urban centers, we need a massive effort to upgrade low wage service jobs in fields like retail, office work, food prep and personal care. More than 60 million American work in these jobs, nearly half the workforce. And they do not pay enough to survive in urban centers.

Turning these low-wage, insecure jobs into higher-wage, secure, family supporting jobs is the only way we can rebuild out middle class. We can’t bring back enough manufacturing jobs to do it; and we can’t educate everyone to be a high-wage knowledge worker. And many of these jobs, like the ones in personal service, can’t be automated. It will be a long time before a robot can bring you food, cut your hair, or take care of your kids or ailing parents.

We forget that we did this before: we turned low-wage, dangerous factory jobs into the good middle class jobs we bemoan losing today. My father also liked to remind me that when he was a kid in the 1930s it took all nine of the members of his family to make enough to get by. But when he came back from his service in World War II, that very same factory job now paid enough for him to get married, have a family and put my brother and I through college. We did it by enabling factory workers to unionize, by creating a social safety net, by linking factory workers’ wages to productivity and other mechanisms. But as a society we realized that the only way to have a middle class was to pay the people making our cars and appliances enough to actually buy those things. And we created a model of affordable suburban jousting to help spur that American Dream.

We can do the same today by upgrading service jobs, and we need to. Who or what is more important to you anyway: the people who make your cars or appliances or the people who take care of your kids of parents. It’s no brainer, actually, when you think about it.

You mention that Trumpism is a backlash—and not just against women, immigrants, minorities, globalism, and sustainability, but against an urban-powered growth model. How so?

I saw it first with Rob Ford in Toronto and I said if it could happen in as progressive and diverse a city as that, more and worse would follow. And it did. First Brexit, then Trump, now the surge in populist across Europe. This is a direct by-product of the New Urban Crisis. In fact, you can’t understand Trump and the populist backlash if you don’t understand the New Urban Crisis. That backlash is the political reaction to winner-take-all urbanism – the growing gap between superstar cities and their advantaged residents and everywhere and everyone else.

You can see it in the vote, which the book breaks down. Clinton took the dense, affluent, knowledge-based cities and close-in suburbs that are the epicenters of new economy. She won the popular vote by a substantial margin. But Trump took everywhere else. In the primaries, his support was concentrated in counties with larger white populations, more blue-collar jobs, larger shares of people who didn’t graduate high school, and also, according to an analysis in The New York Times, with greater shares of people living in mobile homes. In the general election, he took 61 percent of the vote in rural places compared to 33 percent for Clinton. He won 57 percent of the vote in metros with less than 250,000 people, compared to 38 percent for Clinton. He carried 52 percent of the vote in metros with between 250,000 and 500,000 people, compared to 34 percent for Clinton. All told, he won 260 metros, compared to Clinton’s 120. But the average Trump metro was home to just 420,000 people compared to 1.4 million for Clinton.

Why are cities so important for American living standards?

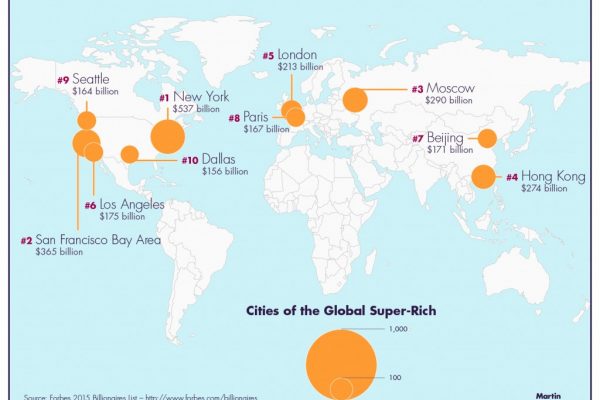

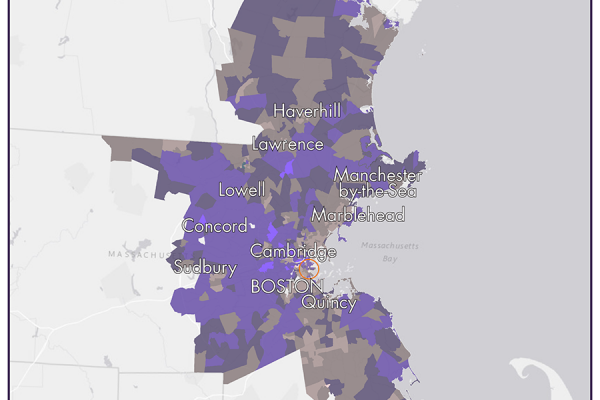

Because they are the epicenters and central organizing units of our economy. The world’s 40 largest mega-regions like the Boston-New York-Washington Corridor produce two thirds of all economic output and nine in ten innovations while housing just 18 percent of the world’s population. Just the Bos-Wash Corridor plus the San Francisco Bay Area account for more than half of all high tech startups in the world. Cities are key to everything form startups and innovation to job creation, rising living standards and a stronger middle class.

Why do Trump supporters sees our great cities as centers of pathology and violence when the reality is that they are our premier platforms for innovation and economic growth?

While Trump poses our great cities as centers of pathology and violence, the reality is that they have become our premier platform for innovation and economic growth. Fifteen of America’s top 20 metro areas are sanctuary cities – and they account for roughly 45 percent of US GDP. The Bay Area, Greater Los Angeles and the Boston-NY-Washington DC corridor generate two-thirds of all high-tech startup companies in the United States. Just two neighborhoods in that city’s downtown attract more than a billion dollars in venture capital investment a year, more than any other nation in the world.

Trumpism or populism is not just about economics or inequality. It’s about geography and race. It’s backlash against women, immigrants, minorities, globalism, and a fundamental check on this urban-powered growth model and on the rising living standards of all Americans. It’s part and parcel of the backlash we just talked about.

Our nation has sorted itself along class and racial lines. Trumpism is a backlash against the urban cosmopolitan creative class and its values of diversity, tolerance, multiculturalism, meritocracy and globalism. It comes from parts of the country that are falling behind economically, that are whiter, less diverse, and which feel threatened by the rise of diverse, global urban places and the people who live in them. And this is the case in the US and around the world. So, the populist mind sets sees cities not as centers or innovation and growth but as the places that are undermining traditional family values. Trump gives this a unique spin. Even though he lives in New York he is unable to see the changes that have happened there. He still sees it as the same kind of distressed city it was back in the 1970s and 1980s when he was cavorting at Studio 54.

You write that an uber-powerful nation-state may have made sense in an era of economically concentrated industrial capitalism, but it’s out of sync with the demands of our clustered and concentrated knowledge economy. What are the first steps that cities can take to limit and counterbalance the power that Trump wields?

The nation-state is an anachronism. It was built for the age of large-scale vertical industry, when we had to unify a production platform (through railroads and highways) and market for mass production industry, when there was a small capitalist class and large exploited working class that needed to be protected and helped. A century ago, a stronger federal government was the path to overcome the graft and patronage rampant in our cities and to expand the infrastructure needed to build a unified nation. A strong central government was in sync with the demands of the large-scale vertical mass production industrial age. As the century progressed through the New Deal through the Civil Rights movement and the Great Society era of the 1960s, federal solutions were the path the expanded civil rights, women’s right, and gay rights and to a more equitable society.

That’s changed fundamentally today. An uber-powerful nation-state may have made sense in an era of economically concentrated industrial capitalism. But, it is out of sync with the demands of the clustered and concentrated knowledge economy.

The new knowledge economy is concentrated and clustered in cities and urban areas. New York, London, and San Francisco have different kinds of economies and different kinds of problems and challenges than places like Detroit and Pittsburgh on the one hand, or Phoenix and Atlanta on the other. To take just one example, their minimum wages need to be much higher in light of their higher costs of living.

There is no one-size-fits all strategy for the very different kinds of places that make up America. Exurban and rural places and big cities and metropolitan suburbs are very different kinds of places. No one strategy can address their very different needs and desires. Dense places need transit; more spread out places need better roads and bridges. Urban policies are best-tailored to local conditions and local needs. A 21st century economic strategy cannot be central or national, but it can be local.

The GOP has long sought to shrink the federal government and shift power to the states and local governments. Do you see the GOP actually moving in this direction if Democrats are on board?

That’s a good thing and a trend we can work with. Conservatives and Republicans have long argued from smaller government, for shrinking the federal control and shifting power to the states and local governments. It is time to hold the to their word. Devolution not only fits the fear of Trump on the left, it fits the GOP’s long run desire to create a smaller national government.

It’s not just people on the left like me or Bruce Katz of Brookings or Benjamin Barber who wrote If Mayors Ruled the World who are calling for devolution of power to states and cities, Joel Kotkin is calling for more localism and Yuval Levin outlines the need for “subsidiarity,” or the devolution of power to its lowest level.

Why would a step into bottom-up governance be more efficient now?

Local governments are more pragmatic than ideological; they have first-hand knowledge of the challenges they face and of the local strengths that they can leverage to overcome them. When I travel around the country and meet with mayors and council people, I cannot tell who is a Democrat and who is a Republican.

Twenty-five years ago, the economist Alice Rivlin made a powerful case for devolving education, housing, transportation, social service, and economic development programs from the national government to the states, whose leaders are closer to the conditions on the ground. This is backed up by a massive amount of research from the OECD, which shows that decentralized local government is more effective and efficient than centralized control. As large corporations realized long ago, decentralizing decision-making to work groups on factory floors is the source of huge productivity gains. Local governments are not only less ideological, they are also more pragmatic and more effective than centralized a national government that see-saws between parties and partisan ideology.

Years ago, when so many business and policy pundits were extolling the virtues of Japanese and Korean economic and industrial policy, one of my Asian students said: “That sort of industrial policy works great when you make the right call, but when you don’t it fails. In the US, you have hundreds if not thousands of local economic policies.” Our states, and even more-so, our cities have long been the so-called laboratories of democracy, where new initiatives and approaches are tried out and honed.

Bottom-up governance is not only more efficient; it gives citizens more choices. Urban economists have long argued that we essentially “vote with our feet,” essentially selecting the communities which best serve our wants and needs. Local autonomy acknowledges those differences, allowing people to choose the kinds of communities that reflect their values.

What is our only path to overcoming our paralyzing political polarization and healing the deep divides that plague our nation?

Right After the election, a very smart reporter asked me a very smart question. What do we do to overcome America’s stark Red-Blue divide? Without even thinking, I shot back immediately: It’s not possible. Our divides are not just about politics; they are baked into the deep structures of the knowledge economy. The biggest problem facing America is not Trump himself—it is the polarization that made him possible. It is a gut-wrenching, four to eight-year cycle of despair for half the country.

Left to unchecked, our current polarization is ultimately a path to mutually assured destruction. Most importantly, devolution and local empowerment can be a path toward mutual coexistence of Red and Blue America. By reducing the power of the federal government, it can reduce the stakes. And by enabling and respecting local differences, it can allow people to live the lives they want to in their communities without threat of federal incursion.

Much of the fear that Trump instills is a product of the vast over-concentration of power in the nation-state. While we can’t wrest the nuclear codes from his control, we can take steps to limit and counter balance the power that he has over our own local economies by shifting more of it away from him.

Finally, where does this movement start? Mayors? Activists?

Cities of course are emerging as the main source of opposition to Trump and his agenda. Half a million people took to the streets in Washington, DC. Some 400,000 marched in New York and there were even more marchers in Los Angeles. Boston drew 175,000 and Chicago 150,000. In total, a staggering 3.2 million people—or about one in every 100 Americans – participated in these protests across 400-plus U.S. cities.

An even bigger fight is looming over immigration and sanctuary cities. Trump’s executive order banning travel from seven majority Muslim countries and suspending refugee programs sparked spontaneous protests at the nation’s major airports that attracted not just angry students and leftists, but elected officials and business leaders. Both of New York’s US senators, several US representatives, and Mayor Bill deBlasio shared the podium with prominent Muslim activists at a protest rally in New York City’s Battery Park. Mayor after mayor of America’s sanctuary cities vowed to protect their undocumented immigrants, even at the price of losing federal funds. And a group of international cities have pledged to provide aid to America’s sanctuary cities if the Trump Administration cuts their funding off.

Cities may be the opposition to, and our strongest bulwark against, Trump and Trumpism, but there are more and better reasons to press for a devolution of power away from the nation-state and to local governments. Devolution of authority and local empowerment offers a more effective way to govern, one that is in sync with our urban power and geographically varied knowledge economy. Moreover, shrinking the power of the nation-state and the imperial presidency and empowering the local is likely to only way to overcome our paralyzing political polarization and begin to heal the deep divides which plague our nation.

This is an area where mayors and local officials can lead. Such a broad bi-partisan movement of mayors calling for devolving and shifting power toward greater local control might well find many allies in Washington, on both sides of the aisle. Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former New York City Mayor has the money to back it. It would give him the purpose and the platform he has so longed wanted in American politics.

America has a huge institutional advantage in its historically flexible system of federalism, which can balance and rebalance power among the federal government, states, and cities. During the New Deal, Franklin D. Roosevelt forged a new kind of partnership between the federal government and the cities. It’s time to do so again, this time putting more resources, power and control in the hands of local government.

The present moment affords a real opportunity to recast urban governance in a way that aligns the underlying nature of economic activity and the challenges it brings with the level of governing authority. Transit and transportation investments, for example, could be overseen by the networks of cities and suburbs that make up metropolitan areas or even the groups of metropolitan areas that make up mega-regions.

It’s time to move away from the outmoded overly concentrated, overly-centralized and dysfunctional political system of today. We can re-balance our vertical separation away from the national and toward the state and local. It may be the only thing that can save us from ourselves.

”Porch Light Books 2020 Best Seller List

”A sweeping narrative of the most significant human movement of our times—global urbanization. Richard Florida lays out with unassailable facts and clear vision the convergence of an urgent human development—the drive for more livable cities and the quest for a more sustainable planet. Clear, compelling, and full of vision.

Martin O’Malleyformer Governor of Maryland and Mayor of Baltimore

”Florida, a whiz at developing metrics…

Andres ViglucciMiami Herald

”One of “The Top Urban Planning Books of the Decade”

Planetizen

”Amazon Best Seller

”Amazon Canada Best Seller

”Amazon Rank #1 in City Planning & Urban Development

”Amazon Rank #1 in Urban Planning & Development

”800-CEO-READ Business Bestsellers for May 2017

”Florida’s book offers a groundbreaking vision for inclusive and prosperous cities and is a call to city dwellers and urban politicians alike to become better-informed and propose and follow through on hard but rewarding choices.

Barbara RomanikWinnipeg Free Press

”Mr. Florida continues to address the most vexing problems we face as a society: politics and poverty, sociology and segregation, innovation and growth, zoning, education, workforce training, gentrification, zoning, taxes and regulation, just to begin.

Christopher BriemPittsburgh Post-Gazette

”Some of Florida’s ideas – give more powers to mayors, resist NIMBYism, cut red tape for builders, construct more transit, push for more urban density – are sensible responses to these evolving urban challenges.

Marcus GeeThe Globe and Mail

”I loved The New Urban Crisis. Richard Florida writes about the tensions and the divides that have emerged within and between cities, between the broader community — and I felt it throughout the book and loved it.

Steve ClemonsWashington Editor at Large, The Atlantic

”A thought-provoking work for those interested in all stages of urban planning and placemaking.

Karen Venturella MalnatiLibrary Journal

”He’s a serious scholar whose ideas must be wrestled with. I’ve found myself in agreement with him more often than not.

John TaltonThe Seattle Times

”Thank you Dr. Florida for your talk and leadership with yesterday’s events at Ohio State. The Lecture and mayoral panel were terrific. We’ve received so much positive feedback.

Janis BrowningOffice of Outreach & Engagement, Ohio State University

”An urban planning rock star

Jake BlumgartPlanPhilly

”I was engaged and energized by The New Urban Crisis.”

Scott SternFaculty Director, Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, MIT Sloan School

”His awareness of urbanity in popular culture and his references to art and politics also make Florida accessible and allow him to engage a larger audience…

Barbara RomanikWinnipeg Free Press

”Like the superstar cities it describes, this book is dense, complex and stimulating. Florida’s well-researched and fluent exposé of inequality is a wake-up call to all the major actors engaged in planning, designing and managing cities in the 21st century.

Ricky BurdettProfessor of Urban Studies, London School of Economics

”I was engaged and energized by The New Urban Crisis.

Scott SternFaculty Director, Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, MIT Sloan School

”Florida provides a wealth of information and analysis.

Robert MorrisSan Francisco Review of Books

”It’s quite thought-provoking.

Amarjeet SohiInfrastructure Minister

”I recommend Richard Florida’s 2017 book: The New Urban Crisis. Rising inequality may be the most important economic issue facing the world today. His detailing the urban dimension of this is striking.

Robert J. ShillerYale University

”Selected by Planetizen for “lasting relevance and excellence in research and rhetoric, will continue to define the ambitions and the shortcomings of the urban planning field in the decade that was the 2010s.

PlanetizenYale University

Urbanist Richard Florida popularised the idea that the creativity economy spurs urban regeneration with his 2002 book

The Rise of the Creative Class. Fifteen years later, creative cities have revived but are plagued with inequality. He tells Dinesh Naidu about his new book, The New Urban Crisis, and how cities can spread the benefits for inclusive urbanism.

The title of urbanism theorist Richard Florida’s latest book–The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class and What We Can Do About It–outlines the defining tensions in our cities today. In earlier writing, Florida defined many of the progressive notions about how the creative class could drive social and economic progress, but these notions have fallen short. In this book, he reckons with the failings and promise of his theories, and suggests course corrections to help cities become more equitable.

In the spirit of the winter reading season, The Hill Times trotted down to the Hill to ask Parliamentarians what books they were plowing through, some of which may appear in our upcoming books special Dec. 18.

Economic inequality is a well-known issue in the United States and around the developed world. Not only has a gulf grown between the haves and the have-nots, but so has the gap between the haves and the have-mores.

Interview with Noah Smith of Bloomberg View on his new book, The New Urban Crisis.

Nearly 20 years ago, urban theorist Richard Florida identified a group of highly-skilled workers whose outsized contributions were driving economic change and development in cities around the globe. His book, “the Rise of the Creative Class” detailed the characteristics of this type of worker and more importantly how to nurture and attract them. Its core findings were adopted by mayors worldwide. The trends identified in Florida’s research contributed to the seismic shifts, growth and revitalization in downtowns large and small. Those changes have not been painless for all involved and have lead to what Florida, in his new book, calls the “New Urban Crisis.” So when Richard Florida asks What the Future, he wonders if developers are recognizing the new realities.

Fortunately, when it comes to cities, there is Richard Florida, director of the Martin Prosperity Institute at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and author of The Rise of the Creative Class, which explained how a new generation of people was reviving ailing industrial centres. Now, he is explaining how that trend is, among other factors, helping to intensify the issues confronting many urban centres. The New Urban Crisis is subtitled “Gentrification, Housing Bubbles, Growing Inequality and What We Can Do About It”, and, while Florida’s analysis of how we got here is unsurprisingly insightful, it is that last bit that is crucial.

Interview with Richard Florida on his most recent book The New Urban Crisis with the Italian daily newspaper la Repubblica.